Inigo Jones: The Welsh Clothmaker's Son

Little is known about the early life of Inigo Jones. It’s thought that he was born in 1573 in London’s Smithfield area to a Welsh-speaking family, the son of a cloth-maker.

Similar to many esteemed architects, his journey began as an apprentice to a cabinetmaker at the onset of the 17th century. Subsequently, with the backing of a wealthy benefactor, he ventured to Italy to hone his skills in drawing and painting, catching the eye of Kristian IV of Denmark during his time there. Upon returning to England after a few years, Jones secured a position at the court of King James I, where he crafted extravagant costumes and stage sets for the grand court spectacles called masques. He collaborated closely with the renowned English playwright Ben Jonson on more than 500 productions, although their partnership was marked by incessant disagreements, as often seen with brilliant minds. Though it is his design for the Queen’s House in Greenwich, commenced in 1616, that we find most beguiling. Here is a description by architectural historian John Summerson:

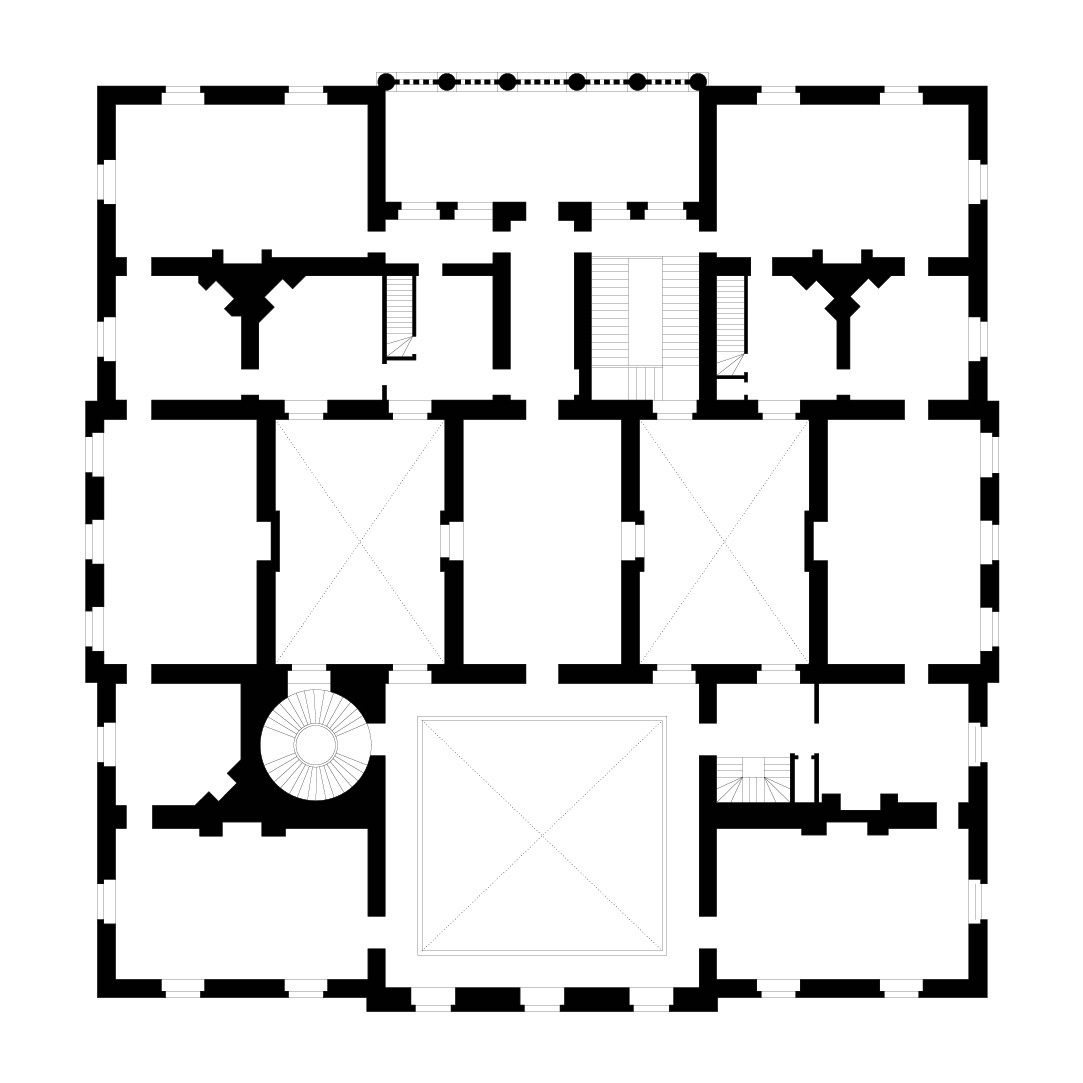

“The house was designed to meet very peculiar circumstances. At Greenwich the gardens of the palace were divided from the park by a public road, running from Deptford on the west to Woolwich on the east. This meant that a royal party proceeding into the park had to cross the road; it also prohibited any effective architectural link, short of a bridge, between the palace and park. In conceiving the Queen’s House, Jones converted this difficulty into an opportunity and designed a double house, half in the garden, half in the park, the two halves connected by a covered bridge. He didn’t not attempt anything spectacular out of the bridge and packed the whole design into an approximate square figure, so that when, in 1661, two further bridges were built, on the perimeter of the square, and almost flush with the outer walls, the division in the design ceased to be apparent without any violence to the conception as a whole. Today, with the road diverted, it is hard to believe in the duality which was such an essential and curious feature of the original conception.”

– John Summerson, Architecture in Britain 1530 - 1830